When Comedy Met Tragedy: the JFK Assassination

It has been 60 years since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy — a national tragedy like very few in the 20th century.

One aspect that hasn’t received much detailed examination in the decades since is how the business of making people laugh was affected by that shocking event.

Before we do that, let’s take a few minutes to look at what was happening in the world of comedy as we entered the 1960s.

At the dawn of the Kennedy era, the world of film comedy rested on shaky ground. The entire decade of the 1950s produced only about a half-dozen comedies that have stood the test of time. In 1960, Bosley Crowther, film critic for The New York Times, lamented how true slapstick, so popular in the silent comedies of the 1920s, and revived via montage tribute films such as When Comedy Was King, assembled by producer Robert Youngston, had given way to bland, suburban comedies like Please Don’t Eat the Daisies. “Considering the pallid quality of most screen comedy these days,” he wrote, “it is gladdening but saddening, we must tell you, to look at When Comedy Was King.”

The critically maligned Jerry Lewis brought true slapstick comedy back to films after its nearly comatose decade of the ’50s. He began his solo career soon after he and Dean Martin parted ways, but it wasn’t until he took full control — writing, directing, starring, edition — that his films took on their special quality (The Bellboy and Cinderfella in 1960, The Ladies Man and The Errand Boy in 1961, and, of course, The Nutty Professor in 1963) even as Lewis was derided for turning them into self-indulgent ego trips. He provided what had been missing from films for so long: an anything-for-a-laugh philosophy favoring silly, often surreal sight gags and a plethora of pratfalls, designed to do nothing more than to keep filmgoers in stitches.

In the meantime, television comedy at the dawn of the Kennedy administration offered a mix for viewers to choose from, including established comedy-variety show veterans like Red Skelton and Jack Benny, and, as always, new sitcoms, most of which were bland and unrelentingly wholesome family scenarios (with some exceptions, such as The Dick Van Dyke Show), as they were just beginning to chip away at the dominance Westerns had on TV since the mid-1950s.

In big city nightclubs, stand-up comedy found itself regenerating as well. New York especially became the breeding ground where a new wave of satirical stand-up comedians began to thrive.

Among those attracting the most attention were Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Bob Newhart, Shelly Berman, Jonathan Winters, Woody Allen, Joan Rivers, and Nichols & May. And, unlike their predecessors, these comedians were not reliant on teams of writers for most of their material (e.g. Bob Hope and those of his ilk), but instead created their own monologues and sketches.

Television gave the public a more immediate connection with important events. The faces of Congressmen and world leaders on the evening news, along with images of conflicts on city streets and foreign battlefields, had become much more real and recognizable to viewers. This global shrinking via TV enabled comedians to drop names and refer to events they knew their audiences had most likely seen on the news the night before. Political and social satire gained popularity, as it produced a post-vaudeville generation of performers who often incorporated current events, politics, and social trends into their routines.

This had the stand-up comedy styles of the time divided roughly into two camps: there were comedians who kept a keen eye on the world, and who used it to sharpen their humor with varying degrees of cynicism (Sahl, Bruce) There was also the more conventional, good-natured camp who played things for laughs, but kept it all relatively harmless and inoffensive (Newhart, Nichols & May, Winters).

In any case, the day of the mother-in-law joke was fast approaching twilight.

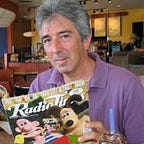

As TV programs such as Ed Sullivan’s and Jack Paar’s provided promising comedians instant access to as many people in a single night as they could in a year’s worth of club gigs, comedy albums saw a meteoric rise in popularity in the first years of the ’60s. The Buttoned-Down Mind of Bob Newhart, a collection of Newhart’s popular one-sided phone conversations, became the first comedy album ever to top the Billboard charts.

Inside Shelly Berman was the first non-music album to go gold. Bill Cosby won the Grammy for Best Comedy Album six years in a row. Allan Sherman’s novelty song, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah,” and his album My Son, The Folk Singer also made big splashes. Just about every major comedy star — and a few minor ones — embraced this medium at the time (by mid-decade, 450 comedy album titles were listed in the Schwann catalogue).

At the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, October 22, 1962 — the night Kennedy addressed the nation about the situation in Cuba — writer/producers Bob Booker and Earl Doud recorded the album The First Family, an affectionate satire of the Kennedy administration and family.

The album starred young standup comedian and JFK soundalike Vaughn Meader and was recorded before a live studio audience — who, consequently, did not hear Kennedy’s speech as it was telecast. However, the cast did watch it, yet still had to perform the comedy despite their anxiety over the crisis.

The album was released in November by Cadence Records, selling more than 1 million copies per week for the first six weeks, and becoming #1 on the Billboard charts for a total of twelve weeks. Meader became a much sought-after sensation, appearing on TV variety programs, and on national magazine covers.

The cast reunited for a sequel album, The First Family Volume Two, released in the spring of 1963, by which time the original The First Family had sold 7.5 million copies and won the Grammy for Album of the Year. The sequel album reached #4 on the charts in June.

In the movie theatres, most significant film comedy of the year, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, opened on November 7. Throughout all of film history, no comedy has matched its grand scale, brilliant cast of comedians, and pure physical energy.

Yes, the art of comedy, as performed in movies, TV, nightclubs, and records, was seeing a definite surge.

Then it happened.

On November 22, President Kennedy traveled to Texas and sat in an open convertible with wife Jackie, and Texas Governor John Connelly and his wife as their motorcade made its way through the streets of the city.

The nation was suddenly plunged into shock and despair with the assassination. It had been over sixty years since President William McKinley was gunned down in 1901, when the nation far less inter-connected, with only newspapers and telegraphs to report that incident to the population. In 1963, the McKinley assassination and the era in which it occurred seemed to lie much further in the distant past than a mere sixty-plus years (Franklin D. Roosevelt had been the last president to die in office, from a brain hemorrhage, in April of 1945).

The first news flashes to interrupt November 22 afternoon network TV programs came at about 1:40 p.m. Eastern time with scant information, limited to the report that both Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connelly had been shot as their motorcade proceeded through Dallas. Regular programming briefly returned, but a few minutes later, the bulletins broke in again with the news that Kennedy was in Parkland Hospital. Not long after that, confirmation came that he had died.

From that moment on, all three major television networks ceased their regular programming to report on the developments. This was to remain the case for the next four days straight, as viewers witnessed the unthinkable — live reports from Parkland Hospital, the sudden, on-air shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby, and Lyndon Johnson’s return to D.C. to take over the reigns as President. The four days culminated with Kennedy’s funeral.

Along with the nation at large, the series of events had an immediate impact on the comedy world as well. With television’s regular programming suspended, the three major networks had precious little time to re-examine the content of the comedies and dramas on their schedules. Executives scrambled to determine if anything that had been planned to air needed to be edited, postponed, or canceled indefinitely, in case a storyline, reference, or joke had suddenly become questionable or in poor taste.

Not every comedy outlet had even a few days to reassess. The assassination prompted a unique and last-minute change for Britain’s popular comedy/political satire program, That Was the Week That Was, created by Ned Sherrin and hosted by David Frost. The program premiered a year earlier, almost to the day, and was soon affectionately nicknamed TW3.

Each week featured a mix of comedy sketches, songs, and mock newscasts covering events from the previous week (thirteen years before “Weekend Update” would do the same on Saturday Night Live), taking aim mostly at British politicians, government policies, world leaders, and entertainment celebrities. It was clever, highbrow, and didn’t condescend to its viewers, who needed to be well-informed to appreciate the humor. The production also used the then-new technique of having the cameras include shots of the audience, backstage activity, and the other cameras taking new positions as various cast members walked on and off the set between sketches. The wide shots of the studio allowed TV viewers to see the nuts & bolts of the production as it was airing live.

The American version of the show, also hosted by Frost, began airing on NBC, on November 10, with a recurring cast including Alan Alda, Buck Henry, Tom Bosley, and singer Nancy Ames, as well as guests such as Nichols & May and Henry Morgan.

The British TW3 was scheduled to air the evening after the assassination, just over 24 hours after the event. When the news reached the cast and crew, the production team was just about to receive a special award at London’s Dorchester Hotel from the Guild of Television Producers. They huddled together backstage to figure out a plan of action.

Ned Sherrin explained, “…Plans were immediately discussed to include a tribute to President Kennedy in the program the next day. We telephoned several of the distinguished writers who work for the program but no final decision was made as to what form the tribute should take.”

Regular rehearsals took place the following morning until lunchtime, but by then it was clear the mood was not conducive to biting political satire; the material they had been working on was scrapped, and the cast was released until new material could be written.

Sherrin explained how the writer proceeded. “First, Christopher Booker came up with the series of personal statements that formed the opening of the program…Herbert Kretzmer produced the opening lines for his song ‘In the Summer of His Years’ so that Dave Lee could start composing the tune; and Bernard Levin agreed to devote his piece to a consideration of the potentialities of the new president. By four p.m. the first two items were virtually completed, and Millicent Martin was able to start learning her song; but two essential qualities still seemed to be missing from the program.”

Sherrin continued, “There was as yet no reference to the grief of Mrs. Kennedy, nor was there any item which caught the atmosphere of an oration, with that heightening of language and formalized distinction that such an occasion demands. Caryl Brahms was asked to write the lines “To Jackie” at about 5:00 pm. in the evening, and Dame Sybil Thorndike agreed to deliver them at 7:00 pm. Bernard Levin started work on the oration at 7:30 — remembering that this was after all a week of anniversary of the Gettysburg Address — and a copy of that address beside him to inform his style. After two false starts he completed the speech at 8:30. It was taken to Robert Lang who was to deliver it, at the Old Vic where he was playing the Player King in the National Theatre production of Hamlet. He came offstage at 9:30 and he and Dame Sybil arrived at the studio just before we finished rehearsing, at the same time that David Frost was putting the finishing touches on his own script.

“The studio audience who had come expecting the usual acid comedy show were warned that we had to change our plans.”

Sherrin described the angst of trying to present the most appropriate material possible under the circumstances. “TW3 is unique among comedy shows in that it tries to record faithfully the atmosphere of a week; to maintain a consistent, witty, questioning point of view; to be outspoken, challenging, and iconoclastic. It is difficult for us to know how valid or how valuable our comments on the late President are, conceived and delivered as they were, in the haste and emotion of the moment; but it has been immensely rewarding to find from letters, telephone calls and telegrams that many people in America who had never seen the program before or perhaps never heard of it found the treatment responsible, precise, pointed, and proper; and that people in England who have watched us regularly and found us in the past provocative and amusing, felt that on this occasion we were consistent.”

Indeed, the somber and reverential nature of the material could be considered surprising, considering how the program was addressing the loss not of its own nation’s leader, but that of one an ocean away.

A tape of the episode was flown to New York, from where NBC aired it on the 24th, and received an appreciative review in The New York Times, noting, “One totally unexpected event was the brilliant program put together by the London troupe of That Was the Week That Was. The satirists scrapped their original plans and quickly compiled one of the most moving of the many analyses of the American crisis. Its brilliance lay in the writing and the hard-hitting performing, an inspired insight into the meaning of Mr. Kennedy’s death in the nuclear age and a generous and perceptive appraisal of President Johnson. The program’s joy was its mixture of warm compassion and cool detachment, a remarkable contribution in all respects.” The Times also reported that about 850 viewers phoned in “to applaud the vigor and compassion displayed in the imported presentation’s incisive appraisal of President Kennedy and its estimate of the potential of President Johnson.”

Otherwise, while all regular entertainment programming in the U.S. had ceased for those four days, the cost of special news coverage by NBC and CBS was estimated to total nearly $4 million in canceled commercials (over $39 million today), and somewhat less for ABC, much of which could not be recovered.

In Los Angeles, comedy playwright Neil Simon was scheduled to negotiate with Paramount Pictures for rights to film his hit play Barefoot in the Park, as well as to pitch his new play, The Odd Couple, as part of the same package. He hadn’t yet begun writing The Odd Couple but was persuaded to pitch it to Paramount based on only a brief description of the premise.

On November 22, Simon stood by his hotel entrance with his agent, Irving “Swifty” Lazar, who was going to drive them to the meeting. As they waited for the valet to retrieve Lazar’s car, another car screeched to a halt, with the woman driving it screaming, “Kennedy’s dead! They killed the president!” Simon thought perhaps it was phony, or that he was watching a movie scene filmed with a hidden camera. But within a few seconds, the reality had become obvious. The doorman and others rushed to her and heard the news bulletins on her car radio.

“We all stood there numb,” Simon wrote in his memoirs, “unable to comprehend what was happening. It couldn’t be true. It wasn’t possible. Irving turned white and said, ‘Jesus Christ.’ There were tears in his eyes and he didn’t know which way to move. People kept turning to each other as if maybe we could do something about it. It was like Pearl Harbor Day only this war was over in ten seconds. Irving finally looked at me and said, ‘Not a good day to talk to Paramount.’ ”

Simon and his wife Joan remained in L.A. for a week. As they were ready to return home, Lazar called with the news that Paramount still wanted to have the meeting. “Irving,” Simon replied, “how can I talk about a funny idea to anyone at time like this? I don’t have the stomach for it and how receptive could they be?”

“This is Hollywood, kid. They can do anything.”

The next morning, Simon was still unsure what to say at the meeting. “Irving took care of all that. There was some talk about the horror of the assassination, then Irving switched the mood and miraculously got things back to business as usual. ‘Neil didn’t want to come today and we can all understand that. But life moves on. Tell them the idea, kid…’ ”

Elsewhere in the entertainment industry, a knee-jerk reaction to the tragedy led to wholesale changes, in some cases without significant consideration. A few examples:

The assassination quickly affected The First Family album, which had been selling like hotcakes since its release. Producers Booker and Doud, along with Cadence Records president Archie Bleyer, had both albums pulled from store shelves and recalled, and had unsold copies destroyed so as not to seemingly “cash in” on the President’s death. Many stores no doubt pulled the LP on their own accord. Both albums remained out of print for decades, until they were finally re-issued on CD together in 1999.

Vaughn Meader’s career famously came to a grinding halt. How could he, or club owners, or record producers ask audiences to laugh at an impressionist — no matter how skilled — impersonating a president who had been cut down in such a way that left the nation in shock and grief?

A story that has acquired almost legendary status involves Lenny Bruce’s first public reaction to the assassination. Some accounts claim he went onstage that very night at the Village Theater in New York City (more likely about a week later, as few venues remained opened that night), and took a long moment to survey the audience before uttering his opening line, “Boy, is Vaughn Meader screwed!” (knowing Bruce’s verbal proclivities, he most likely used a word other than “screwed”).

Meader had in fact been working on a new comedy album did not include any impersonations of Kennedy, but by then he was already typecast by his own uncanny way of sounding (and looking) like the slain president. It was this very talent that became the albatross around his neck he would never successfully discard and became a virtual show business pariah overnight. His scheduled appearances on TV and live venues were cancelled, and Meader cancelled a number of them himself, knowing the country would not be the least receptive to his famous schtick.

As The New York Times reported days after the assassination, “A decision was automatic in the case of a Joey Bishop show taped November 15 and planned for use in February. With Vaughn Meader, Danny Thomas and Andy Williams as guest stars, the whole show involved Mr. Meader’s impersonation of President Kennedy. The tape has been erased.”

Mort Sahl was another comedian greatly affected by the assassination, and it’s been noted that his own career also suffered for it, albeit due to his own obsession with the possible conspiracy behind the killing.

Sahl was riding high at the time. Woody Allen, whose own star had been on the rise, bowed to Sahl as the true innovator among standups of the period. “He was absolutely like nothing anybody had ever seen before…each joke he made was not just a golf joke, for instance, but a genuine insight into politics, into social relationships between men and women…The whole face of comedy changed completely.”

After the assassination, however, Sahl became obsessed with the possibilities of an intricate government/military plot behind the killing, and even worked in conjunction with New Orleans prosecutor Jim Garrison to gather evidence of the conspiracy. But this came at the cost of Sahl’s professional obligations as a comedian. When he did return to the stage, it was to incorporate large passages from the Warren Commission report of the assassination into his act, turning what had been a comedy act into a lecture on how evidence was being hidden from the public. Critic John Leonard wrote in the New York Times in 1978, “He went strange after the assassination of John Kennedy…And the talk shows stopped wanting to hear him go on about the grassy knoll, the two autopsies, the washed-out limousine, Lee Harvey Oswald’s marksmanship, Jack Ruby’s friends. He wasn’t funny. He was also, eventually, unemployed, and bitter, as he made clear in his memoir Heartland. Would he survive? Would any of us?”

Yes, both the nation and Sahl survived, and in time, he did lighten up and return to his patented way of making stinging observations about the rich and powerful. He enjoyed a modest resurgence in popularity until his death in 2021.

As for the world of comedy as a whole, the tragedy of the assassination, and other such traumatic nationwide events to follow, taught us about the nature of collective grief and mourning, and how to slowly and thoughtfully emerge from it to reclaim our familiar lifestyles — including, and importantly, the need to laugh again.

Until next time…

If you enjoyed this article, please click the “follow” button and follow me on Medium (no charge) for more of my articles on popular culture, music, films, television, entertainment history, and just plain old history.

You can also become a member in the Medium Partner Program for a modest fee to help support my writing. https://garryberman.medium.com/membership

Please visit www.GarryBerman.com to read my other articles and synopses and reviews of my books. You can order them via the links to Amazon.com.

A small selection of my nearly 100 previous online articles:

“It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” 60th Anniversary | by Garry Berman | Nov, 2023 | Medium

“Retro Review: ‘Local Hero’ at 40” by Garry Berman | Medium

“Television Stars Who Went From Hits to Flops” | by Garry Berman | Medium

“The 747: When Getting There Was Half the Fun” | by Garry Berman | Medium

“Celebrating 100 Years of The Little Rascals” | by Garry Berman | Medium

“How a Kids Band in Barcelona Rekindled My Love of Jazz” | by Garry Berman | Medium

And many more!